Friedrichstraße Bayreuth – The Street of Five Composers

The Margravine Wilhelmine of Bayreuth was Monarch, Director of the Opera, Philosopher, Writer and much more besides, yet it was music that lay especially close to her heart. Her most opulent work is the opera entitled ‘Argenore’, and she even composed a harpsichord concerto, only part of which still survives unfortunately.

With its sense for harmony, the magnificent splendour of Bayreuth’s Friedrichstraße certainly bore the stamp of Wilhelmine’s influence upon margravial court architect Joseph St. Pierre. During the time of construction of today’s Steingraeber Haus, Joseph St. Pierre passed away, and Carl Philipp Christian von Gontard, his assistant who was to become even more renowned, completed the majestic building with an undoubted glimpse into a future style of architecture: Neoclassicism.

From 1827 onwards Robert Schumann was absolutely besotted with the literature of Jean Paul; the writer lived opposite Steingraeber Haus. Jean Paul died in 1825 and so it was his widow who received the 18-year old Schumann in 1828. Again and again, he drew inspiration from Jean Paul’s works, which is particularly evident in his work ‘Papillons’.

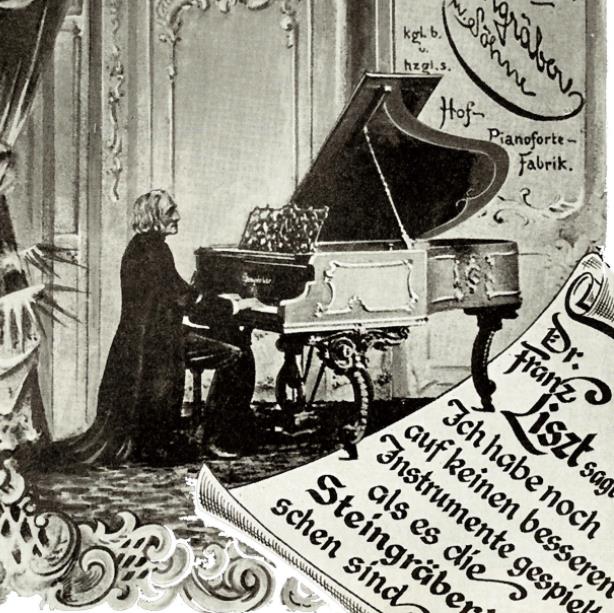

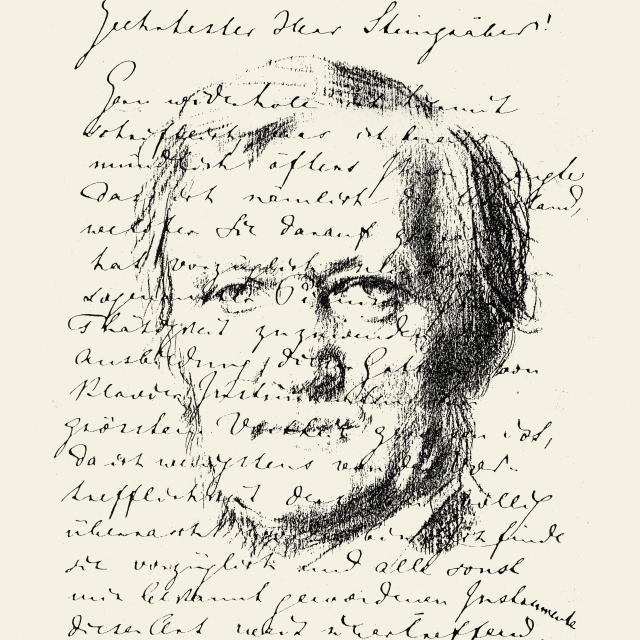

Richard Wagner visited Friedrichstraße (including Steingraeber Haus) around the year 1871 and from 1872 even lived in the immediate vicinity, in the so-called ‘Dammwäldchen’ opposite the Steingraeber factory. He would use the Steingraeber Hall at No. 2 Friedrichstraße, during which time, in 1876, Franz Liszt came to Bayreuth and would also be associated with Steingraeber. From 1878 onwards, Liszt was a frequent guest in the salon situated on the ‘belle étage’ of Steingraeber Haus, known today as the ‘Rokokosaal.’

Anna Thekla Mozart, recipient of many discreet letters from her cousin Wolfgang Amadeus, also lived in Bayreuth, spending her twilight years from 1814 until 1841 at No. 15 Friedrichstraße. She was involved in an evidently stormy affair with Wolfgang Amadeus in 1777 and 1779.